The Cult of Director Ida Lupino’s The Filmakers Movies

Article thanks to www.cultfilmalley.com.au. *Contains Spoilers

British-born actress and director Ida Lupino (1918-95 stroke and colon cancer) lived her the life the hard way which ended in alcoholic oblivion… Yet she was the first woman in Hollywood to direct herself in a movie and the first to direct a film noir. Many of the movies she directed had a social conscience or message and despite their low-budgets have been revalued and remain watchable today.

Ida was the daughter of British stage performers Stanley Lupino (1893-1942 cancer), whose family was big in the theatre, and stage performer Connie Emerald (1892-1959), which was the stage name for Constance O’Shea, who was one of five music hall-oriented sisters …. Connie’s sister Nell Emerald (1882-1969) produced sound films in the early 1930s in Britain and also co-wrote a couple… and was perhaps an inspiration for Ida.

It was in the early 1930s that teenaged Ida got her first job in the movies when she was unexpectedly chosen over her mother at an audition and she quickly became known as “England’s Jean Harlow”. She eventually made the move to Hollywood where her successful performance as a spiteful cockney artist’s model in The Light that Failed (1939) resembled that of Bette Davis (1908-89 breast cancer) in Of Human Bondage (1934). As a result, Ida remarked self-deprecatingly that she was the “poor man’s Bette Davis” at Warner Bros. studios. Ida’s look resembled and reminds me of Scarlett Johansson (1984-) and her voice sometimes sounds like Lauren Bacall (1924-2014 massive stroke) … Ida was an original though and was known for her portrayals of femme fatales or of women from the wrong side of the tracks.

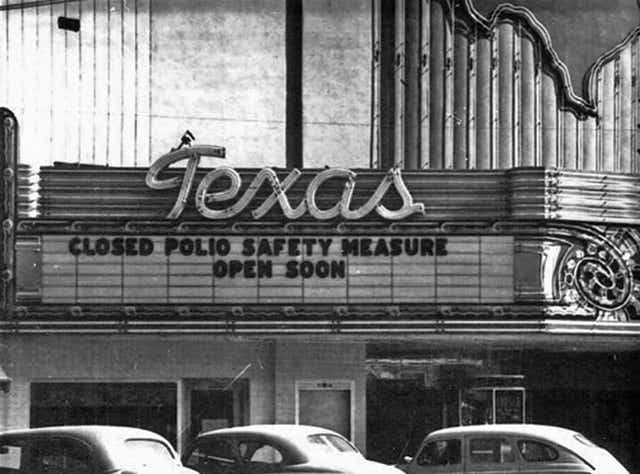

In 1934, she and her career survived a bout of polio and it was in hospital and at home taking bed rest that she realised her possible intellectual potential in terms of creation. She even wrote some music during this period which was later performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in concert.

“I realised that my life and my courage and my hopes did not lie in my body. If that body was paralysed, my brain could still work industriously… If I weren’t able to act, I could write… even if I couldn’t use a pencil, I could dictate,” she remembered about that period.

“I really want to create…. Stories, personalities, pictures… Sooner or later I should like to remain behind the camera instead of in front of the camera,” she also said in another interview.

She would go on to become a star in such films as They Drive by Night (1940), High Sierra (1941) The Sea Wolf (1941) and The Hard Way (1943) with stars such as Humphrey Bogart (1899-1957 throat cancer) and John Garfield (1913-52 heart attack). The Hard Way, which was released shortly after the death of her father, seemed to be a bit of a veiled look at her father’s, and possibly her mother and her family’s, infidelities and the infidelities within showbusiness as a rule. Or the bohemian notion of sex outside of marriage. The Production Code kept it pretty tame though.

“I knew a family of five sisters that were in love with the same man, unfortunately, he was in love with five other girls,” is the raciest line which captures the flavour of the movie and hints at the Emeralds. The film title was given a nod in Ida’s later movie Hard, Fast and Beautiful (1951) which also had an ambitious and rejected mother figure.

She also starred in one of her favourite movies Ladies in Retirement (1941) with her then husband Louis Hayward. It was a Victorian film noir about madness.

After a period of coming up against Jack Warner and often being suspended for not taking certain roles, Ida left Warner Bros. in 1947 and freelanced. It was the film Road House (1948) in which she did her own singing of the song One for My Baby (and One for the Road) which probably best summed up her smoking and drinking tough persona. Her short fringe hairstyle in that movie must have been the rage as Veronica Lake’s (1922-73 hepatitis) return to her peek-a-boo hairstyle in Saigon (1948) failed at the box office that year while bad girl Ida’s Road House made millions for 20th Century Fox. But since the awards for her acting weren’t forthcoming for that movie, in which she also really looked bored and world-weary, and because she had some clout in the industry, she decided to move into film production.

She formed Emerald Productions, named after her mother and aunt, and it made a crime drama entitled The Judge (1949) directed by Elmer Clifton (1890-1949 heart attack or cerebral haemorrhage). The film is forgotten and Ida didn’t contribute officially to the screenplay. It is described as ‘artsy’ for its symbolism by some reviewers and it challenged The Production Code with the shooting of a disabled child and his cute dog by a nut who didn’t like the child’s constant violin playing. There is also a two-timing wife, oh so shocking, but not within the show business community – and real life! This would later relate to Ida’s personal behaviour herself and the second last movie she directed The Bigamist (1953) which summed up slyly both herself and her then husband’s attitude to marriage and sex. The Judge tried hard to top its opening and it succeeds in being compelling as a result in an exploitative way thanks to Anson Bond’s (1914-79) script. There’s also a hint of a social conscience and psychology amid the exploitation but it doesn’t pretend it wants to solve any problems to a great degree like Ida’s later movies. Clifton was used to dealing with addiction and white slavery in his low budget movies and he lacks the sensitive touch Ida would give her films.

After, The Judge, together with her second husband Collier Young (1908-1980 car accident), who she married in 1948, and who was a production executive at Columbia Picture, they formed The Filmakers production company. Their films had a distribution deal with RKO which was under the misguided management of Howard Hughes at the time and would use creative accounting practices when it came to the net profits of The Filmakers’ movies.

The films of The Filmakers would be an alternative to the glamour and melodramas produced by the studio system and would have a semi-documentary feel. Ida would direct five movies for The Filmakers and officially co-write four of them.

She had learned about filmmaking by observing the professionals as she worked as an actress and credited her technique and scriptwriting ability on her first movie through conferring with actor and director Michael Gordon (1909-93), who was the grandfather of actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt (1981-). Cinematographer Archie Stout (1886-1973) was also a positive influence and he worked with celebrated director John Ford (1894-1973 cancer) around the time he did The Filmakers’ films. There is also a report that editor William Ziegler (1909-77) also helped guide Ida through her first movie as director.

She said as an actress she had been bored on set while “someone else seemed to be doing the interesting work.”

Anyway “nothing lay ahead of me but the life of a neurotic star with no family and no home,” she also said of herself in Hollywood and a couple of the characters she played.

It was more about reality and the films produced by The Filmakers were shot on location and avoided soundstages. It was also more about not ‘who’ was in the picture but ‘what’ was in the picture, as the actors of The Filmakers movies were generally unknown by Hollywood standards. Ida, as the director of several of the movies, was a kind of precursor to John Cassavetes (1929-89), who was another independent director whose movies which began in the late 1950s became increasingly self-indulgent. The Filmakers films were one of the first in Hollywood to use product placement to earn credit and shots were planned to minimise retakes and to use as little film as possible.

The first film they produced was Not Wanted (1949) aka Shame, which wanted the title Unwed Mother but this was rejected by The Production Code. The movie was about young single women getting pregnant out of wedlock – a controversial subject back then but one which couldn’t be ignored.

The director was meant to be Elmer Clifton again and Ida had co-written the script with her husband Collier. Clifton had a heart attack during pre-production and since the budget was so low at $150,000, Ida stepped in as the director.

Clifton among his exploitation films also directed dozens of low-budget westerns in the 1940s and also made Republic Picture’s most expensive serial Captain America (1944) but his work was low-budget and without distinction until The Judge where he seemed to be inspired. In the end it was a blessing that Not Wanted had Ida at the helm.

“For women, directing is almost impossible to do…. Unless you are an actress or writer with power,” Ida said in retrospect about becoming a producer and then a director.

Not Wanted stars Sally Forrest (1928-2015 cancer), who seems to resemble Ida, which is possibly why she was chosen as a surrogate Ida for the first movies produced by the Filmakers. Forrest would appear in two more films directed by Ida… Never Fear (1950) and Hard, Fast and Beautiful (1951).

The credits start with “Ida Lupino presents…” as, at the end of the movie, Clifton gets credit for directing Not Wanted because Ida wasn’t a member of the Directors Guild of America. She would become a member in 1950. Incidentally, it was that year that she presented an Oscar to Joseph L. Mankiewicz (1909-93 heart attack) where the director quipped Ida was known as Irving on her application form as she was the only female director in the Directors Guild who was working at the time. In fact, the only one other female director that was possibly in the guild was Dorothy Arzner (1897-1979), who had worked back in the late 1920s and 1930s and retired in 1942.

Forrest’s character in Not Wanted faces the capital offence of kidnapping following her snatching a baby from a pram while wandering the streets in a daze due to mental illness… Told in flashback from her jail cell, where another character muses madly that she got “ten years for talking to myself”, Forrest’s character Sally – to underline the reality, it uses her real name – tells her story, which has this teenager fascinated by a jazz pianist at the place where she works. She stays out all night with him much to her mother’s worry… and leaves home in the wake of a fling with him that very evening.

“You don’t seem very glad to see me,” she says to her crush when she turns up on his doorstep after she has met Drew, played by Keefe Brasselle (1923-81 liver disease), on the way to town on a bus. Drew’s a war veteran with a plastic leg, although you wouldn’t know.

The hard-drinking and smoking pianist cum artist tells her he didn’t have marriage in mind but more of just a casual fling known to bohemians in showbusiness and he splits for South America or the next town.

Instead of morning sickness, Sally has a fainting spell at a carnival with Drew and the doctor is called to her boarding house where he says: “You’re going to have a baby” as he goes to fetch Drew who he assumes is her husband.

“I have no husband…,” she says and as the precredit card says at the beginning of Not Wanted: “This is a story told 100,000 times each year” and Ida knew through her research that most of them were teenagers and some girls were as young as ten years old.

Fleeing a possible relationship with Drew – the doctor kept his confidentiality – Sally walks the streets dazed and confused and in penury until she gets involved with a church run institution.

“We’re your friends,” says Mrs. Stone of The Haven Hospital after she asks Sally if she wants to keep her baby. And so, Sally meets other teenaged unwed mothers there.

The film shows it is not the end of the world if you get pregnant in 1949 and that there is help… and understanding to be found. But they also show it is a time when babies were given up by their mothers unwillingly because they knew they couldn’t support them and that they would go to a better home.

After giving birth, with a scene never before seen on screen which shows a mother’s point of view in the operating theatre, Sally gives up her baby and regrets it. It was often the case that the babies were taken from their mothers without even the chance to hold them.

And so, Sally wanders the streets again in a daze and “kidnaps” a baby.

“I just wanted to hold him for a while,” she tells the assistant District Attorney and thanks to the understanding mother of the baby, Sally is not charged and released from custody.

The dramatic ending has Sally flee from Drew, who has spotted her on the street. Drew is humiliated as he stumbles and falls due to his plastic leg as Sally is running from her own humiliation in his eyes… In the end they embrace.

Apparently, the film made its money back in the first two weeks of its release and ended up grossing over a million dollars. Ida was invited to discuss the film on national radio with former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962 cardiac failure). Not Wanted exploits unwed mothers in an understanding and positive way and, as a result, is not an exploitation movie.

The success of this film legitimised Ida as a director and with confidence in herself she and Collier wrote Never Fear (1949/50) aka Young Lovers which is about the effects of polio in the community. It is, in a way, an autobiographical account or possible imagining of Ida’s bout with the disease should it have been more severe. It is also a plea to the community about understanding and accepting disability. Ida apparently got polio from an unsanitary Hollywood swimming pool.

“This is a true story… photographed where it happened,” the film opens and there is credit for a song Why Pretend? which can be seen to be about the stigma of disability and the trauma of it being hidden away in institutions. The film, to its credit, shows that the disabled can find love and a place in the community beyond the institutions set up to care for them.

Once more the stars are Sally Forrest and Keefe Brasselle and they are a pair of dancers who plan to marry after Keefe’s character Guy proposes and she has plans to make him a great star as behind every great man there is a great woman… But before this can happen, Sally gets a stiff neck, headaches and fever. “It’s suspected polio,” according to the doctor.

“I’ll never walk or dance again,” Sally tells Guy bitterly as she gets a private room in a facility dedicated to the rehabilitation of polio victims.

There’s the famous sign Fight Infantile Paralysis with a picture of President Franklin D. Roosevelt who was suspected to have suffered from polio which was why he was confined to a wheelchair.

Ida’s first credited directorial effort was shot on location at the Kabal-Kaiser Rehabilitation Unit in Santa Monica and was made before the release of the polio vaccine in the mid-1950s. California had an outbreak of polio in 1934-35 – when Ida got it – and again in 1948-49 and so it was a current issue in the community and contaminated swimming pools were again cited as the cause in The New York Times. In 1952, a couple of years after the film was made, over 3000 people died of polio in the United States while over 20,000 were left paralysed. Most were children. Due to Jonas Salk’s vaccine, it has now been totally eliminated in the United States.

“You are going to walk,” a doctor tells Sally, who doesn’t believe him and weeps after he tells her he still became a doctor but had to give up dreams of becoming a surgeon due to polio afflicting one of his arms.

She befriends Hugh O’Brian (1925-2016), who is a wheelchair bound patient in the facility where the treatments seem to be of the modern variety espoused by Elizabeth Kenny (1880-1952 Parkinson’s disease). Kenny opposed the immobilisation of patents limbs with plaster casts and braces. Instead, her revolutionary treatment used hot compresses and exercises. A romanticised movie version of her life Sister Kenny (1946) starring Rosalind Russell (1907-76 breast cancer), who would star in Ida’s last directorial effort The Trouble with Angels (1966), was a major box office flop for RKO.

“Are you sure you are not doing this just for me?,” Sally asks Guy about their relationship and the fact she is now disabled and unable to walk. Why pretend?

Never Fear doesn’t hide the facts about polio and the film is a demystification of the illness and institutional care for those who suffer from it. It is a positive film about the survivors who were the forgotten people hidden away from a public that were perhaps afraid they might catch polio if they mingled. Never Fear was a courageous attempt to combat the fear of polio in the community… and it also dealt with sexuality.

Sally stabs a clay sculpture she is doing during art therapy and O’Brian asks what she was thinking? … “Nothing. Nothing at all.” And he replies: “That’s what I thought.”

There’s a square-dancing sequence with people in wheelchairs which shows the sense of community among the thousands which suffered polio over the years before the vaccine became available. It reminded me of the scene from Coming Home (1978) with the wheelchair bound war veterans playing basketball. It took years for Hollywood to grapple with a film about paraplegia and the fact the disabled are sexual beings as well.

Marlon Brando starred in The Men (1950), which was released just after Never Fear, where he played a war veteran who has lost the use of both his legs. The Men got an Oscar nomination for Carl Foreman’s (194-84 brain tumour) screenplay shortly before he was blacklisted as a communist. Never Fear was too cheap to ever be considered for an Oscar and its message too real or deemed exploitative. Its bold symbolism was probably also seen as banal to the upmarket film critics and award show voters of the day. Ida’s work, perhaps like her child Bridget, were seen as kind of illegitimate in the eyes of legitimate critics!

Sally and O’Brian have a blossoming friendship but Guy barges in with his wedding ring as Sally tells him: “I’m a cripple… That’s what’s the matter with me!” Behind Guy, as she tells him to leave, is a life-size sculpture of a satyr with the pipes of pan. This symbol of the God Pan is connected to fertility and spring – and sexuality. Sally’s hysterical ‘panic’ that she will never have a normal sex life with a normal man is also symbolic, as that word is derived from Pan.

Her character is soul sick as a result of her crippling illness and she is unable to come to terms with it, while Guy is driven to distraction and drink at his real estate office where he plays with a doll’s house and uses his bandaged fingers as symbolic walking legs.

Henrik Ibsen’s (1828-1906 strokes) play A Doll’s House is symbolic of a woman’s self-fulfilment, as well as her life being stymied by traditional roles. The traditional role of the cripple is to be seen as invalid to society. The affair between a disabled person and one who isn’t was not seen as a possibility as it is not traditional. Sally thinks she can never be the homemaker or dancer she once intended. She carries a chip of her shoulder.

On another level and, in reality, Ida broke from the traditional role of a woman not being a director, nor behaving within the confines of a marriage. There was no pretending about Ida as a symbol within the filmmaking community – it was both sexual and intellectual. Although the symbolism may be a bit obvious in some of Ida’s work, it means well, as it impresses and challenges the average viewer’s ability to think while still showing the harsh reality of life.

When a crippled friend in the facility reveals she and her husband married after her bout of polio, Sally’s determination to walk is renewed… and she decides she really wants to leave the institution and lead as normal a life as possible… which gives her the hope she needs to remain positive and succeed.

So, Sally walks with a cane while she learns that O’Brian is a different case and will never walk again nor leave the institution. The pair have a scene together where she wears pearls, which maybe a symbol of the bride she will become… but it will not be O’Brian’s.

When she leaves, there is also an indication of a disabled person’s sense of possible institutionalisation as a result of their disability, as Sally looks back and nearly goes back as she is afraid to leave the rehab centre and embrace a life in the outside world with Guy… which she does when the pair hug. Never Fear is a universal tale of rehabilitation as well as the acceptance of a disabled person in the general community.

Ida Lupino’s next movie would be her masterpiece in PART TWO

SheSociety is a site for the women of Australia to share our stories, our experiences, shared learnings and opportunities to connect.

Leave a Reply